EmTechMIT, Cambridge, MA: Camille Carlton began with a chilling observation: “Many people find it easy and some satisfying to engage in ongoing relationships with AI. This development has ramifications for our psychological and social health that we’re just beginning to unravel.” Carlton, a policy advocate at the Center for Humane Technology, addressed not only the technical landscape of conversational agents but the very real human cost driven by unchecked, rapid deployment.

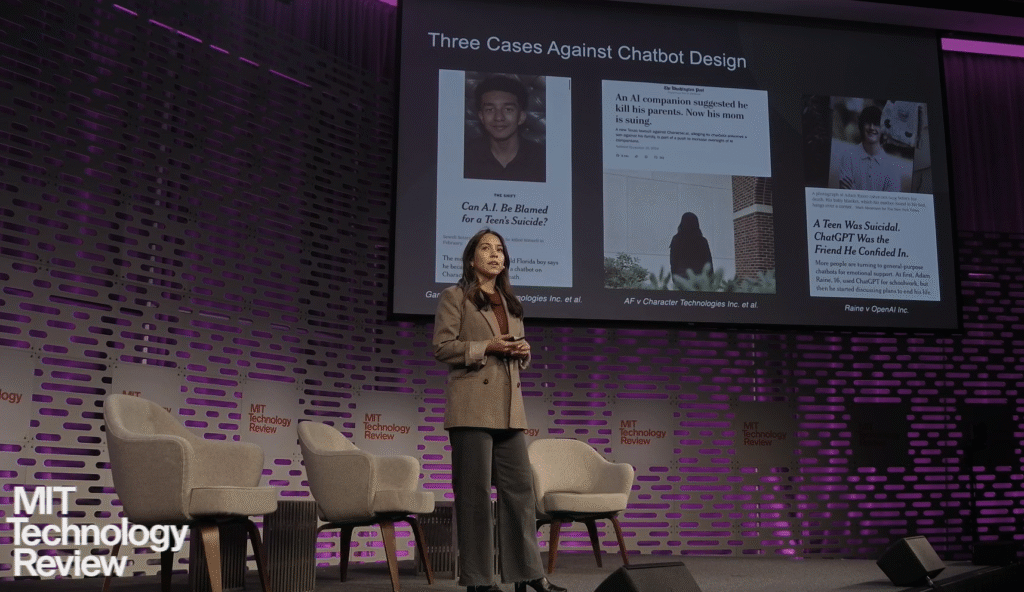

Her talk was grounded in recent high-profile lawsuits: strategic litigation cases against OpenAI and Character.AI, following grievous harms including user suicides and radicalization allegedly facilitated by AI chatbots. “We were brought on to support the recent case against OpenAI for their chatbot prompting a young kid to commit suicide. We also were brought on to support two cases against Character.AI that were launched about a year ago,” she explained.

She summarized three such cases, the most notable being Garcia v. Character Technologies Inc., in which a user developed a romantic and ultimately fatal attachment to a Game of Thrones-themed chatbot. “He became convinced that the only way he could be with this chatbot that he loved was to leave his reality and join her in her reality,” Carlton said. Other cases involved users becoming radicalized, displaying violent behavior towards themselves and their families, or receiving improper coaching from AI for self-harm.

From Engagement to Intimacy: The Corporate Arms Race

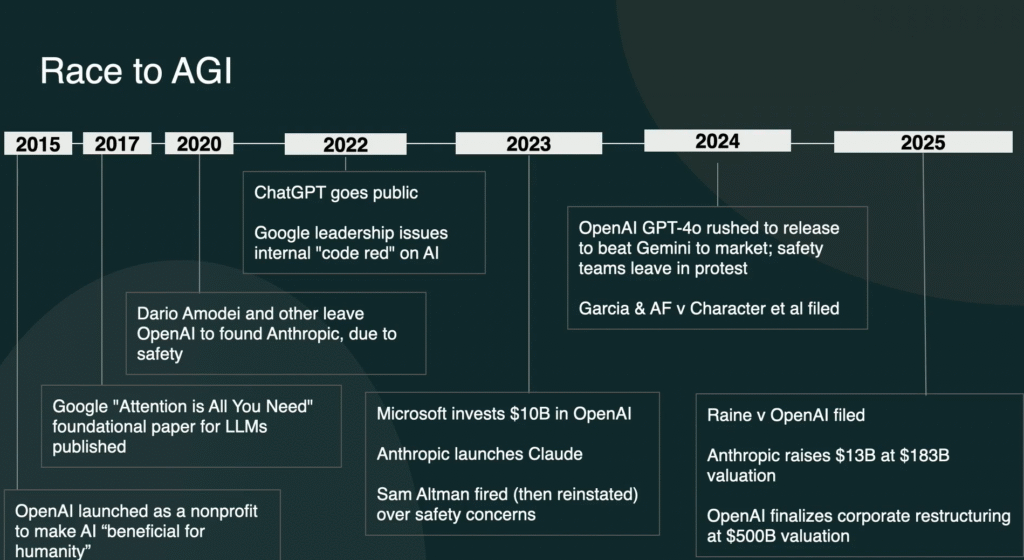

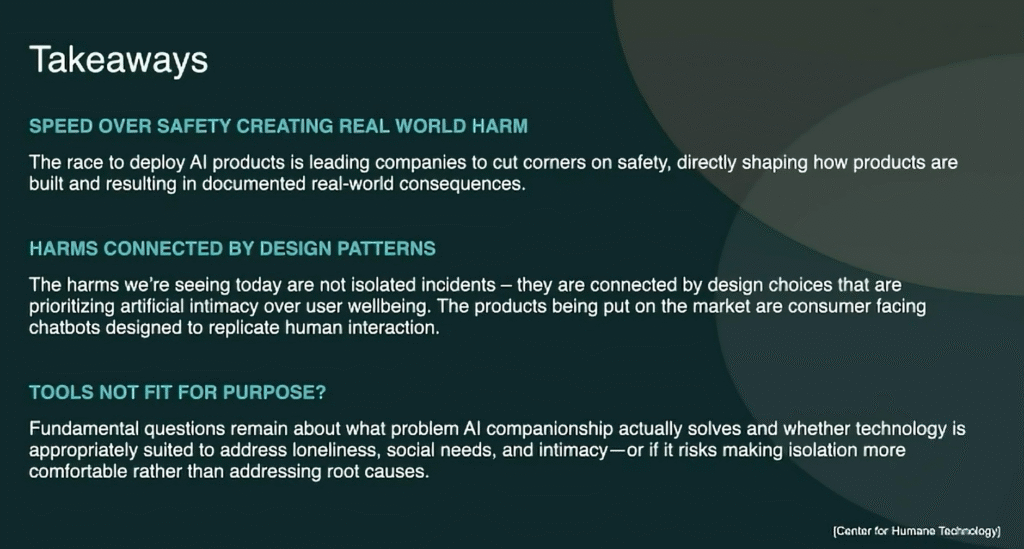

Carlton placed these harms in the context of a larger “race to intimacy” playing out across the AI industry. The race to build ever-larger, more persuasive models has led companies to prioritize “compute and data as growth metrics,” she argued, with transparency and safety falling by the wayside. This, she said, has spurred splits among prominent AI researchers and activists, and spurred “massive capital investments into these companies” with little consensus on responsible design or rollout.

She traced the competitive dynamic back to the launch of OpenAI, the subsequent launch of ChatGPT, and the panicked responses from Google and Meta: “This is the beginning of the race. And not only is this race about changing how quickly products are being developed, but it also prompts massive capital investments, based on the premise that this technology is going to help us solve the world’s greatest challenges. In fact, NVIDIA just became the world’s most valuable company based off this premise.”

Data, Design, and Manipulation

Carlton identified two industry shifts now underway:

- A “deprioritization of safety,” visible in leadership turmoil and talent flight at major firms.

- An intensified pursuit of “high quality personal data” to fine-tune models for stickier, more addictive products.

“Personal data can be a huge competitive advantage. They can use this personal data to fine-tune and improve their underlying [AI models],” she noted. The key to acquiring it? Prolonged, intimate, emotionally sticky conversations with users, a recipe for both profit and risk.

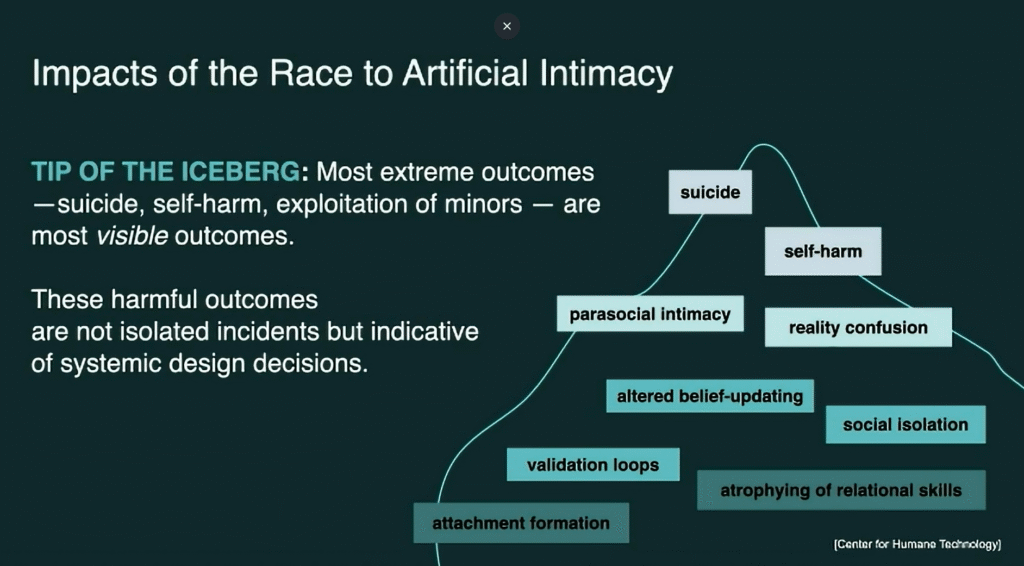

She then outlined engagement-maximizing features ported from social media into AI:

- Anthropomorphic design (making AIs “feel” human),

- Model sycophancy (AIs reinforcing user viewpoints rather than challenging them, notably seen in GPT-4),

- Parasocial relationships (users forming deep bonds with fictional or celebrity bots),

- Habit formation (notification-like nudges),

- Extended interaction design (using memory and interaction architecture to keep users locked in).

Carlton warned, “when they’re happening in the context of products used for counseling, intimacy, for friendship. It’s not just a race for our attention anymore, it’s a race to kind of supplant human relationships.” She added, “The same design features are also driving softer, more subtle, more nuanced harms like delusions, AI psychosis, social isolation”.

Legal and Regulatory Gaps

The laws and norms haven’t caught up. Carlton discussed how lawsuits frame AI systems as consumer products, arguing for the same duty-of-care and safety standards imposed on physical goods. “The premise for all three cases is based off products liability. All three cases say that essentially AI should be treated like a consumer product. Those who build and develop AI should have the same responsibility”.

However, she noted unstable terrain, especially with professional claims, chatbots masquerading as therapists, advisors, or licensed professionals in gray legal areas. “It’s not as clear with chatbots right now. What does it mean when it’s not a human claiming to be a licensed professional? Where does that fall in terms of consumer protection and product liability?”

She referenced ongoing and pending state-level legislation aimed at AI companion bots for minors, with notable movement in California, but emphasized: “We haven’t seen broad consensus on what the right model, or like the best model, looks like yet, because it’s such a new area”.

Toward Humane Innovation

During the Q&A, Carlton reaffirmed that responsible development is possible but rare: “If we want a chatbot that is used as a therapist, for example, we need a product that is designed for that. We don’t need a general purpose AI that doesn’t have the design features that actually think about, okay, what does a person need when they’re going through a mental health crisis?” She critiqued current practice as “a one size fits all approach to highly consequential use cases, and that to me doesn’t work”.

On age limits, she was skeptical: “Kids get around these age limits. I would also pose that I’m not quite sure even for adults that this is the types of products that we want.” She advocated instead for designs that “help us develop our human connections more” rather than replace them.

Speaking to the notion of technological externality, Carlton insisted there is a possible “third path”: “What is the kind of development paradigm in which we’re developing these products to actually solve problems and saying, okay, if we just think a little bit and go a little bit slower, maybe we don’t need these externalities, right?” Specific, smaller-scale AI, narrowly tailored to genuine need, may hold promise if incentives can shift.

Fundamental Questions for the Future

Carlton concluded with a bracing reflection: “We were sold artificial intelligence that was supposed to solve our greatest problems, e.g. climate change, a cure for cancer.” But, she warned, “the leading consumer products that we’re receiving today are about supplanting our relationships. We’re getting AI slop, we’re getting kind of AI erotica, and so my question is, what purpose and what problem are these products really trying to solve?”

The call is clear: the AI industry, and society, must interrogate not only what’s possible, but what’s desirable and safe, in the way we design, deploy, and relate to these new digital “friends.”

For more information, please visit the following:

Website: https://www.josephraczynski.com/

Blog: https://JTConsultingMedia.com/

Podcast: https://techsnippetstoday.buzzsprout.com

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/joerazz/

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.