Month: July 2018

-

Artificial Intelligence and the UK vs. US Approach

Originally published on Legal Insights UK & Ireland By Joseph Raczynski, edits, questions and preface by Ann Lundin and Joe Davis. Artificial intelligence will threaten most jobs at some point soon—and new jobs will emerge’ The impact of innovative technology is undoubtedly going to radically reshape the delivery of legal services in the years ahead. To…

-

Classification of Cryptocurrency: Coins, Tokens & Securitized Tokens

Originally published in the Legal Executive Institute. By Joseph Raczynski One of the most contentious debates in the cryptocurrency world surrounds classification of blockchain-based digital assets, tokens and cryptocurrencies. A panel at the recent Thomson Reuters Regulation of Financial Services Conference discussing the basics of cryptocurrencies examined this argument. With more than 1,650 cryptocurrencies or tokens trading in…

-

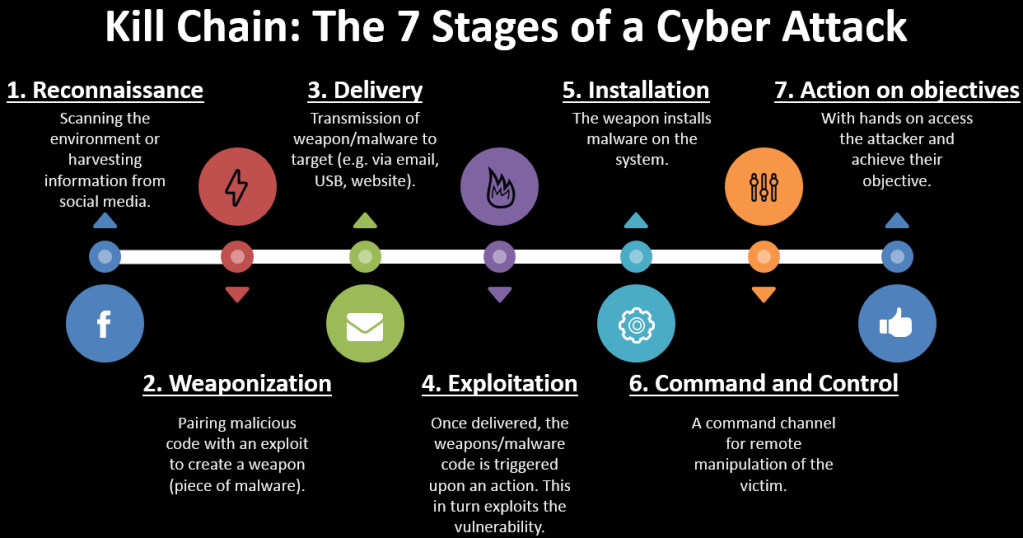

Kill Chain: The 7 Stages of a Cyberattack

Originally published in the Thomson Reuters Tax & Accounting Blog By Joseph Raczynski In our new world reality where cyberattacks are a daily occurrence and every organization must focus on critical infrastructure surrounding cybersecurity, businesses have begun to think like the military. How can we defend our enterprise? To that end, it’s not surprising that companies…